When I asked the security guard at the Congress Hotel in Chicago to see the original rooms that building contractor and engineer Victor Falkenau had constructed in 1892, he dropped the paperwork in his hands onto the desk and told me to “Come along, come along.” He led me along the marble corridors of this modern hotel to the gold elevator doors engraved with a leaf motif. In the elevator, he told me he’d just celebrated forty years of working at the hotel and he’d seen just about everything that’s gone on there. We got out on the eighth floor and strolled down the hall until he opened the door to the room where Al Capone had inhabited. Most visitors clamor to see this notorious room. They visit his hideaway during tours about haunted places in Chicago. Some hotel guests have claimed to have seen Scarface roaming the hallways at night. Another famous person, America’s first serial killer, H.H. Holmes, hung out in the hotel lobby eyeing pretty young women at the time of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.[i]

The guard had never heard of Victor Falkenau, the man who had built the spot where he was standing, but he told me all about Capone. I couldn’t believe that a Roaring Twenties gangster who had ruled Chicago’s gambling, prostitution, bootlegging, bribery, robbery, and murder rings and a con artist lady killer had achieved greater fame than the man who put up the hotel, my great-grandfather.

I asked again to see any remnants of the hotel when Victor had built it when it was known as the Auditorium Annex. I needed details for the book I’m writing about his life and impact on Chicago’s development. Many buildings constructed during the city’s architectural heyday in the late 19th century have been demolished. I’d observed only contemporary design since I’d strode through the revolving door on Michigan Avenue. I questioned how much I’d find.

Victor had to finish the Auditorium Annex―ten stories of gray granite rising to the sky packed with shops, restaurants, and offices on the lower floors and five-hundred guest rooms above―by May 1, 1893, less than a year after taking the job. On this day, the World’s Columbian Exposition celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus discovering America would welcome tourists from Bulgaria, India, Japan, France, Persia, and other corners of the world, as well as those from podunk towns to bustling cities across the United States. Some of the wealthiest, high society visitors would stay in an elegant room at the Annex.

In May 1892, a year before the first throngs of tourists would pour into the fair, the Auditorium Annex was just a blueprint. Victor advertised in newspapers for masons, brick layers, carpenters, plasterers, and hod carriers to begin the largest and most prestigious job since he had founded his company V. Falkenau and Bro. nine years earlier. If he could get this job done on time, it could solidify his reputation as one of the city’s most skilled, reliable builders. It could contribute to his legacy in Chicago. At the same time, it could also show to the world that Chicago was the hotbed of strife and sympathetic strikes across building unions. This possibility threatened to sully his success.

The Auditorium Annex, designed by architect Clinton Warren, would mirror Adler and Sullivan’s Auditorium Hotel and Theater across the road at Michigan Avenue and Congress streets. The Auditorium Hotel―the tallest structure in Chicago, the largest in the country, and the first multi-use facility―made architects, investors, and developers around the country swivel their heads toward the architectural innovations cropping up in Chicago. When the Auditorium was completed, capitalists rushed in to build new skyscrapers replete with offices. They funded the construction of the Chicago Institute of Art, the Field Museum, and libraries to make Chicago a hub for business, arts, and culture.

In October 1892, architect Warren requested the commission for overseeing development to extend the building lines farther onto the sidewalk. It was denied it. Victor waited while the architect re-jiggered the design.

Chicago newspapers were already creating a lot of hype around the new luxury hotel, claiming in November 1892, “The new Auditorium annex…is attracting a great deal of attention.” Two of the Vanderbilts from New York had already reserved suites for the entire six months of the fair. The reporter exalted the hotel’s novel technologies saying, “It will be too much effort for patrons of the hotel to walk from one to the other…so a moveable sidewalk will be constructed in a tunnel under Congress Street connecting the two places, so that when they are overcome with ennui, they will have an amusement that is better than a merry-go-round.”

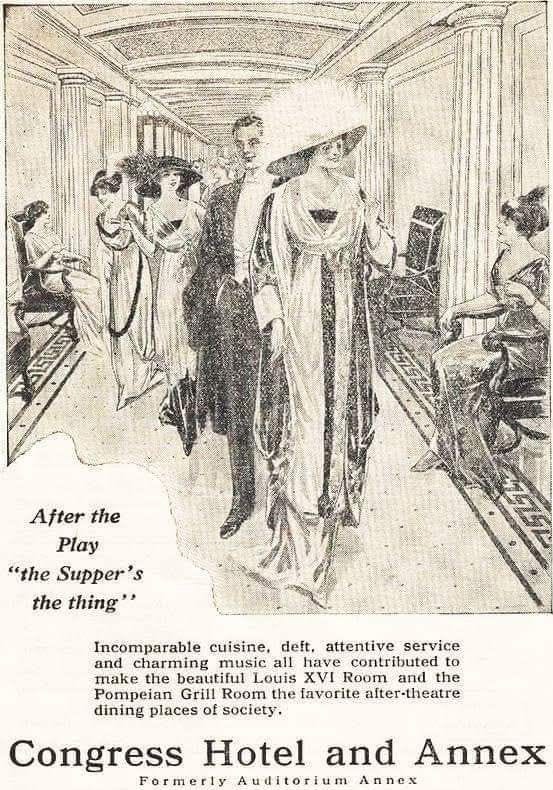

Victor halted work again when the architect decided against the underground moving sidewalk. Instead, he sketched a subterranean marble passageway connecting the two Auditorium buildings. They called it “Peacock Alley” after the glass enclosed walkway at the Waldorf in Manhattan. New Yorkers peered through the glass to watch the city’s upper crust “strut their feathers” as they entered the elegant Palm Room to dine. Now fancy hotels around the country wanted one.

Three weeks before the exposition was to open, four thousand men belonging to thirty unions walked off the Columbia Exposition fairgrounds. Mechanics, plasterers, and cabinet workers throughout the city joined them in sympathy. That same day, one thousand ornamental iron workers at another site went on strike when their employers rejected their appeal for an eight-hour workday. Marble workers at the Art Institute just down the street from the Auditorium Annex quit laying mosaic on the floor in support of their fellow union members at another construction site. With sympathetic strikes across building trades, Victor faced the possibility his men would not show up at all. He had three weeks to go.

On May 1, 1893, the opening of the fair and the day the Auditorium Annex was supposed to receive its first guests, a hundred union plumbers laid down their wrenches at the Annex. They weren’t going to come back until Victor raised their wages from $3.75 to $4.50 a day. He refused. They quit. An increase of that proportion would exceed the budget and cut his profit. Besides, if he gave in, a wage hike could set a precedent. Hiring non-union men but risking strikes by union men protesting the scabs was the only option.

The next day, the marble cutters packed up their tools and marched out of two buildings, the Auditorium Annex and the Monadnock Annex. The marble cutters got mad because the stone had come from Italy and not from Tennessee, Vermont, or another marble-producing state. They also protested that prison workers had sawed the slabs. That was their job.

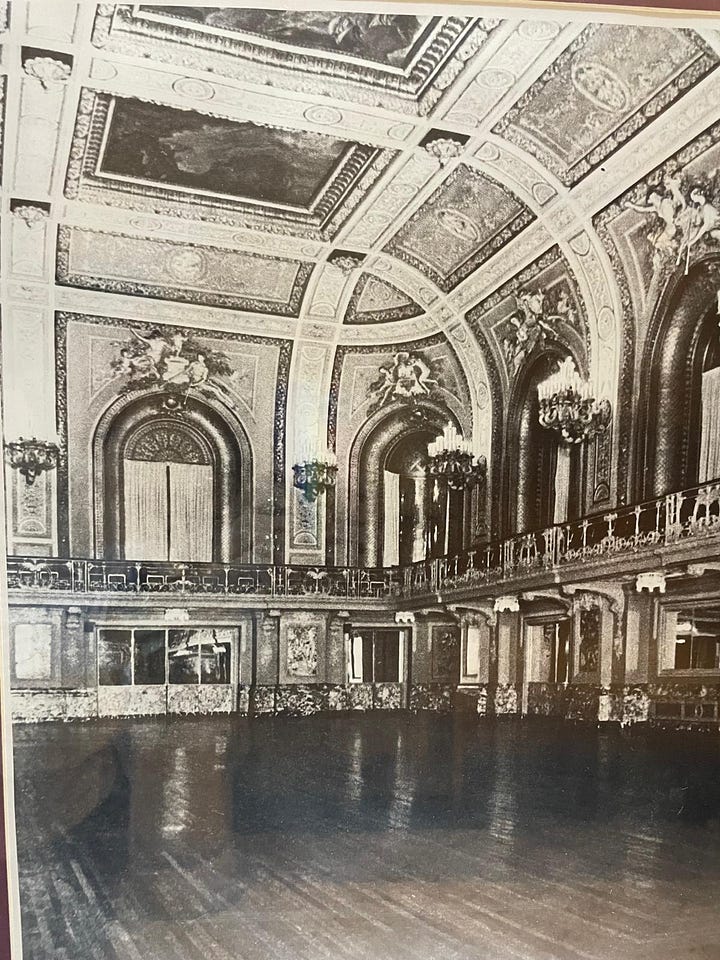

After the threatened and actual walkouts, painters, plumbers, iron welders, carpenters, and other laborers at the Auditorium Annex finally cleaned off and put away their tools a few weeks after the fair’s opening. Since Victor didn’t complete the building on May 1 as stipulated in the contract, he may have had to pay a fine for each day late. Nonetheless, the Vanderbilt family had already unpacked their luggage in the suites that were ready for visitors. They and other monied guests took their seats under chandeliers and frescos in wood paneled dining rooms and perused menus highlighting roast and broiled meats. They chose between fowl, buffalo, antelope, bear, and mountain sheep. They selected “ornamental dishes” such as boned quail in plumage, partridge in nest prairie, and blackbirds. After dinner, they strolled around the Pompeii room admiring the Tiffany fountain and pool.

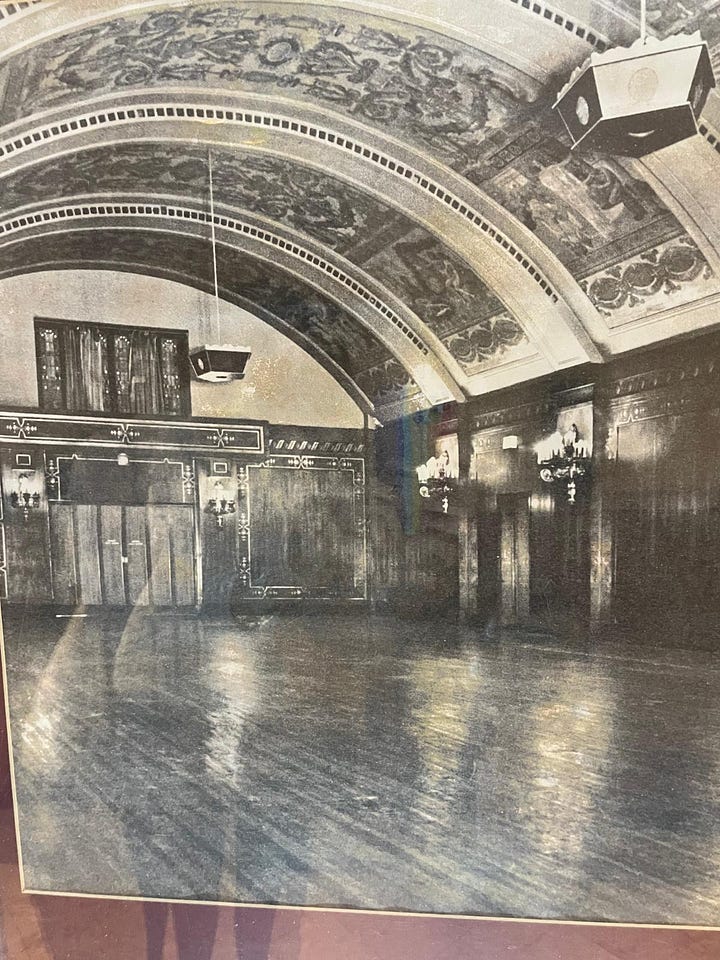

Shutting the door on Capone’s hangout, the guard accompanied me to the other end of the hotel to see something old. When he opened the doors to the Florentine Room, I practically pranced across the wooden floors. Chicago’s elite had paraded through this same entrance in their fanciest attire adorned with precious jewels. Here, they picked up their heels to the German, quadrille, waltz, and the new craze, the two-step. Dark wood paneling with a lighter inlay covered the walls. Sconces lit up the murals covering the curved ceiling.

My own dancing around didn’t last. I learned that the Florentine Room came after Victor’s time. The North Tower that Victor had built and the subsequent South Tower addition made the Auditorium Annex one of the most elegant hotels in the world. It earned the reputation as the “home of presidents,” including William Howard Taft, Teddy Roosevelt, William McKinley, and others. Taft also set up headquarters at the Congress Hotel for the 1912 presidential campaign. One Chicago newspaper said of the place, “You can’t spit without landing on a politician.”

Erecting this ten-story structure in seven months amidst changes in the blueprints, strikes, and threats of walkouts while hiring and supervising hundreds of union and non-union laborers gave Victor the reputation of being a dependable contractor who completed buildings on time―or almost. He parlayed their esteem to other illustrious buildings. For the Western Electric Company, he constructed in 1904 some of the 150-acre Hawthorne Plant in Cicero outside Chicago. Shortly thereafter, he set up shop in Pittsburgh to build a facility for the same company. While there, he erected in 1906 the Frick Annex to model the Frick Building, the tallest skyscraper in the city, and designed by Daniel H. Burnham, prominent Chicago architect and the Director of Works at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

After thanking the guard at the end of my tour, I dragged my feet onto Michigan Avenue. I hadn’t seen any original rooms. I missed ornamentation and decorative light fixtures that belonged to the original Annex. Photographs and sketches would have to suffice. Though not much of Victor’s hand remains inside the Auditorium Annex, the outside of this massive building is a statement to his legacy. It enabled him to erect more buildings in Chicago and other fast-growing cities, embellishing their beauty and stimulating their growth.

[i] Check out Erik Larson’s book The Devil the White City for more on the evils of H.H. Holmes and the building and architecture initiatives related to the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893.

There’s nothing quite like visiting the places of our ancestors. To be able to visit the hotel Victor built, walk the same hallways (even if they don’t look the same), and soak up the vibe of the place must be a magical experience. I’m so glad you were able to do that… and share the experience with us!

Another fascinating story Andrea! Were you able to unearth what compromise Victor and the workers reached that convinced them to return to work? And I’m curious when and why the name changed to The Congress Hotel - or maybe I missed that bit of detail? It will be so great for you to stay there! No ghosts though, I hope.