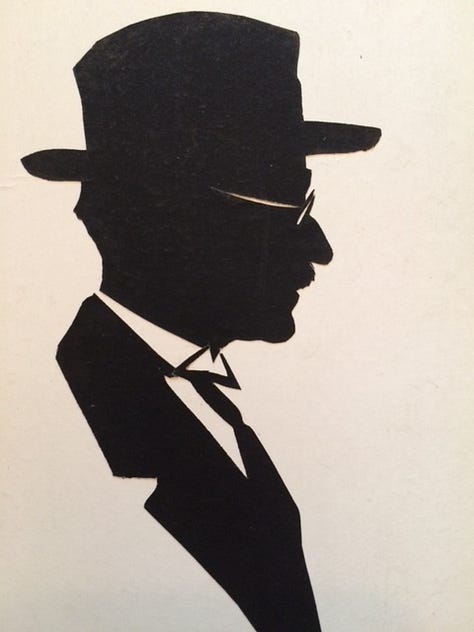

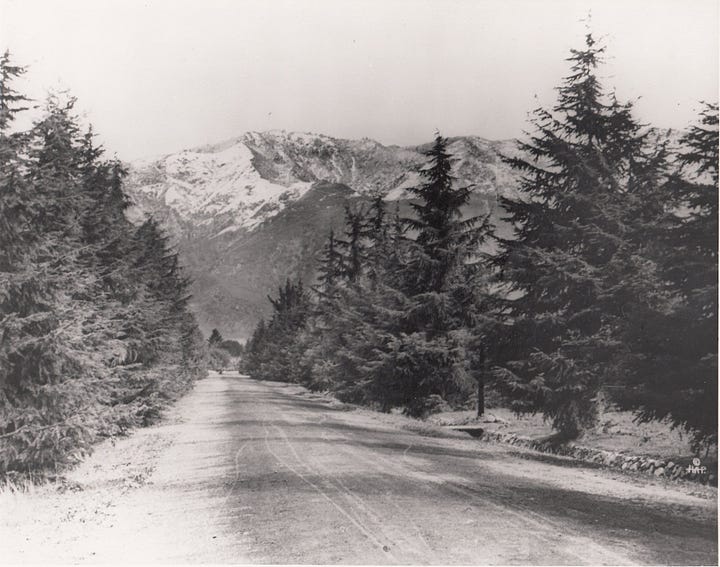

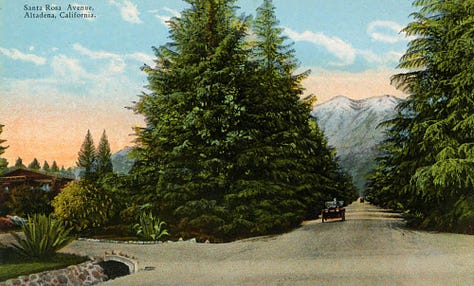

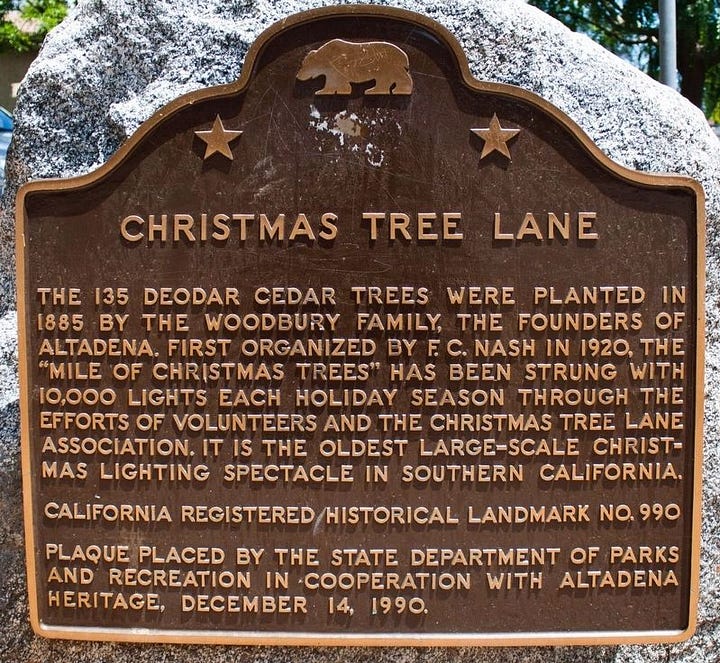

Victor Falkenau fiddled with wires, light bulbs, wooden planks, and pliers in the backyard of his home in Altadena, California to create a Star of David. It had to be large enough to string between the first two deodar cedar trees lining the town’s Christmas Tree Lane. He had been for weeks taking apart strands, screwing bulbs in and out, and re-wiring to have the star ready by the first lighting of the trees, Christmas Day 1920.

Victor was tinkering with the most visible adornment on the lane. This inaugural year only the first quarter of the mile-long Santa Rosa Avenue would be illuminated. Local newspapers called the upcoming tree lighting event “probably the most novel Christmas spectacle in the world.”

Sixty-year-old Victor had recently moved from Chicago with his wife and three daughters to Altadena, fourteen miles from Los Angeles. Grape vines and orange, olive, date, avocado, and walnut trees surrounded the town.

Altadena was no Chicago. It did, however, give Victor another opportunity to make a name for himself. Here perhaps he could bring back some relevance to his career as a renowned building contractor in the Windy City.

Victor brought to bear on this simple but significant task his thirty years of experience as president of Falkenau Construction Company. He had supervised building residences for the wealthy. He had put up thirteen-story skyscrapers, including the Chicago Stock Exchange and the Congress Hotel. He constructed plants for Western Electric, the largest producer of telephone and electrical equipment for AT&T. He erected much of Western Electric’s 2.5 million square foot Hawthorne factory. He applied his expertise from creating the infrastructure of Gary, Indiana for U.S. Steel where his firm helped raise in 1906 a new city out of sand dunes.

Victor worked with one of Altadena’s illustrious citizens, Fred C. Nash, founder of Nash’s Department Stores in adjacent Pasadena, to ready Christmas Tree Lane for its first lighting. Nash expected the illuminated trees and star to attract more shoppers to his Pasadena store.

Victor hammered the frame and positioned the lights to shape a Star of David. The firemen the city had volunteered to place the lights hung it between the first two trees of the lane. Victor may have designed the star as a tribute to his Jewish roots.

For the Christmas Day festivities, Nash brought in members of the United Church Brotherhood and the YWCA to sing Christmas carols. A band played sacred music. Hordes of people on foot and in automobiles admired thousands of red, green, blue, and white lights wrapped around the deodars.

Now that Victor had brought more light and beauty to Christmas Tree Lane, he set out to do the same for the town. With few streetlights, cars ran into pedestrians after dusk. Thieves lurked unseen behind trees. With no sidewalks, pedestrians stumbled over ruts and roots they couldn’t see, even on a moonlit night.

Two years after the Christmas lights dazzled the townspeople, Victor, as president of the Altadena Civic Association (ACA), tried to convince them that streetlights would make the town safer. But residents thought Altadena would turn into bustling Pasadena. They wanted their rural village to stay the way it was.

Victor invited a renowned lighting engineer from General Electric, Walter D’Arcy Ryan, to an ACA meeting to appease the community. Ryan was a leader in the illumination of skyscrapers, including the first one to shine at night, in 1908, a tower in the Singer Building in Manhattan. In 1912, he had lit up the General Electric Company building in Buffalo. He had designed the lighting system along Broadway in Los Angeles.

At the gathering, Victor told Altadena taxpayers that General Electric was testing a new bulb along forty miles of road between Schenectady and Albany to see if it was bright enough to race automobiles at night with the headlights off. This was the same bulb the ACA was considering for its tree-lined streets, he told them. “If Altadenans decide to install this type of lamp it will not only furnish better street lighting that is possessed by any city in the country,” it would also cost about a third of the price of poorer lighting.

In June 1923, residents voted 244 in favor and 85 opposed to “bringing the most modern highway lighting system in the United States” to their town. The city installed 267 bulbs 700 feet apart, while the ordinary lights on the main street would be placed 150 feet apart.

After the system was installed, Victor paced the streets after dark looking for malfunctioning bulbs. One night, he came across a crowd standing on a street corner. He stood on the periphery to listen to people complaining about the streetlights. Shortly thereafter, an article in the South Pasadena Courier Newspaper said that after the installation of streetlights and other improvements, Altadena had developed into “one of the most picturesque dwelling places in California.” It featured a fine water supply, a gas supply, and splendid highways and streets. “…one of the most efficient improvements is the remarkable street lighting system.” Many properties were now out of reach for “the man with an ordinary income.” Complaining stopped.

The timely appearance of this article may not have been coincidental. Perhaps Victor had deployed his savviness in using the media to sway public opinion just as he had done in Chicago as the spokesman to the press when he represented over 1,200 contractors during the construction strikes in the 1890s.

The 104th lighting of Christmas Tree Lane took place on December 7, 2024. Volunteers started in October and worked over ten weekends to string lights around 135 deodar cedars for nearly a mile along Santa Rosa Avenue. Over 50,000 cars coming from all over the country pass through annually. Christmas Tree Lane is on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also a California State Landmark.

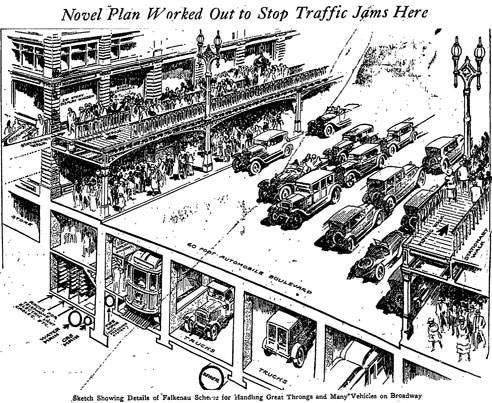

In Altadena, Victor cooked up other bold visions to improve the welfare and prosperity of the region. For Los Angeles, he proposed a plan of moving sidewalks and multi-level roadways to relieve traffic congestion. He devised a scheme to protect against flood damage. He argued for Los Angeles’ industrial development and shipping facilities to make the harbor the center of the country’s Pacific business. This came to be in the 1930s with the Port of Los Angeles and the adjacent Port of Long Beach. He fought for ways to ameliorate air pollution interfering with the ocean view from Altadena’s Mt. Lowe.

Though these progressive ideas, which are still useful today, didn’t materialize, Victor’s Star of David and streetlights contributed to Altadena’s growth and prosperity. He didn’t make as big a name for himself in his new home, but he left these legacies that helped make this farm town what it is.

Here’s a poem Victor wrote shortly after his arrival in Altadena. He frequently scribed silly verses to his daughters when they were children. He applied this practice to other things he loved.

We left the East to seek a home

In a neighborhood less thornier.

And after many days of search

Discovered California.

We sought a home in Foothill Land

With a view of Catalina

And a panorama oh so grand

That’s up in Altadena.

No fog was there to blur your panes

Clear air to aid digestion

And made red blood run through your veins

Which puts a home beyond question.

Thus, Altadena’s the place to roam

To seek her for the greatest wealth

Which is a cheery happy home

Accompanied by unbounded health.

Who wouldn't like a Christmas tree lane in their scenic and little developed coastal California town? Good to hear that there was some lightness and whimsy in the man.

An endlessly curious and creative fellow. Thanks for the continued stories, pictures and research.